In Switzerland when we first heard reports of the coronavirus in China, we only half listened, but when our neighbor Italy announced outbreaks, we were all ears.

In Switzerland when we first heard reports of the coronavirus in China, we only half listened, but when our neighbor Italy announced outbreaks, we were all ears.

The close proximity and community spread of a life threatening virus has Europeans on edge. Most citizens held their fears in check until the Italian outbreak, then within hours illness knocked on our doorstep. Our anxiety stepped up a notch.

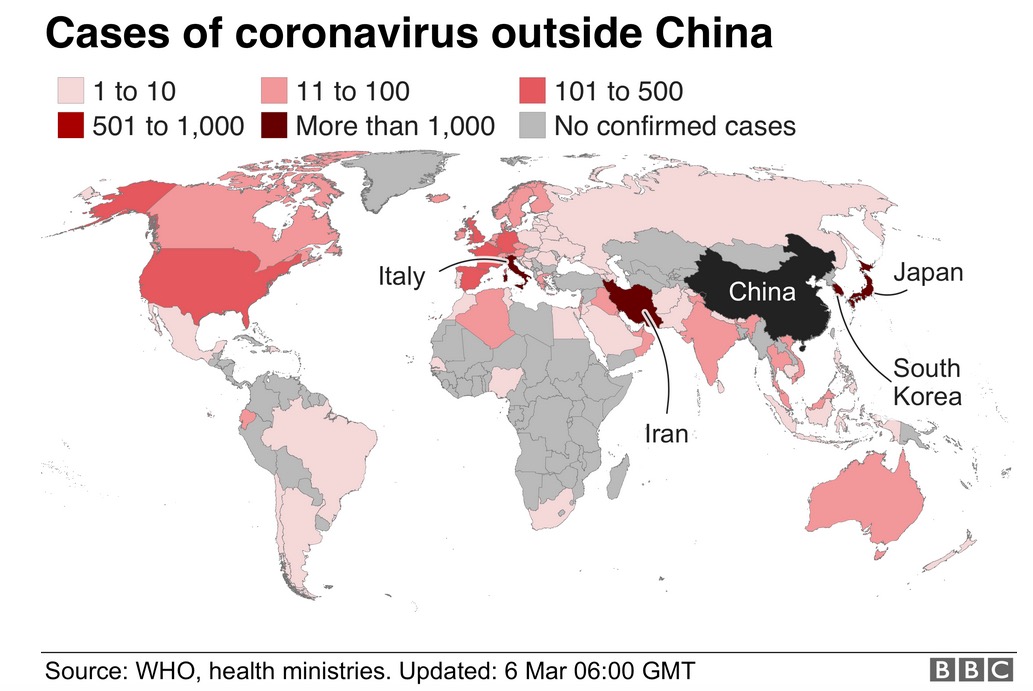

figures valid as March 6, 2020

Surrounded by Italy, Austria, Germany, and France, hundreds of thousands of people cross our borders daily to work in Switzerland. At my former work place, the International School of Geneva, 140 different nations are represented, many of whom live across the French border. Exposure is inevitable.

Suddenly news flashed across Europe in different languages as nations grappled with how to best handle the crisis and contain outbreaks. For the first time ever, Switzerland immediately cancelled its world famous Geneva International Motor Show and forbid public events of more than 1000 spectators including popular soccer and hockey games. France limited gatherings to less than 5000. Both countries immediately shut down schools and shops where clusters of coronavirus broke out. Leaders of European countries reacted quickly, calmly and sensibly.

Meanwhile across the Atlantic, Trump’s initial reaction was to minimize its impact. At his campaign rally in South Carolina, he proclaimed that the coronavirus was the new “Democratic hoax”. By promoting “fake news,” he only added to public confusion and mistrust.

COVID 19 is so new, much remains unknown: incubation period is uncertain and asymptomatic patients become silent carriers. Countries close borders, quarantine citizens, and try to curb public panic.

Medical experts have trouble understanding and predicting outcomes. Even so, international researchers are moving forward so quickly that vaccine might be possible within 12 to 18 months instead of 10 to15 years.

With medical personnel overworked in every country and the public’s anxiety rising, we need to get the facts straight. Worldwide public health and safety should be paramount on any leader’s agenda especially a leader as powerful as the US President.

Fortunately the highly respected Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, is now serving as a member of the White House coronavirus task force to provide facts and clarify misconceptions.

Global health experts like our friend, Dr. Jonathan Quick, former chair of Global Health Council and long term collaborator of theWorld Health Organization (WHO) have been solicited by news agencies around the world such as ABC .

In The Guardian, he offers valuable insights, proposes feasible solutions and provides hope for the future.

His book, The End of Epidemics published in 2018, predicted the present day scenario.

His book, The End of Epidemics published in 2018, predicted the present day scenario.

“Jonathan Quick offers a compelling plan to prevent worldwide infectious outbreaks. The End of Epidemics and is essential reading for those who might be affected by a future pandemic―that is, just about everyone.”―Sandeep Jauhar, bestselling author of Heart: A History

As the WHO scrambles to predict outcomes, produce tests and develop vaccines, we need to listen to the voices of those who know best.

For a world leader to put a personal spin on such a deadly and disruptive global crisis for political leverage is dangerous. Political differences must be put aside, scientific knowledge must be shared and transparency between countries must prevail to contain a world epidemic with such dire consequences.

Regardless if we live in the Americas, Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East or Australia it behooves us all to remember pandemics don’t discriminate.

It is in humanity’s best interest to adhere to the collective advice of the world’s best scientific minds.

Ever since I found out that my paternal lineage goes back to the 12th century Clan Mackenzie, I dreamed of following their trail from Eilean Donan Castle on the west coast across the Scottish Highlands and the Kintail mountains to Castle Leod on the eastern shores.

Ever since I found out that my paternal lineage goes back to the 12th century Clan Mackenzie, I dreamed of following their trail from Eilean Donan Castle on the west coast across the Scottish Highlands and the Kintail mountains to Castle Leod on the eastern shores. Mackenzie’s, once the strongest clan in the north of Scotland, reigned for centuries. From rich, warlords to cash strapped landlords, their story portrays the end of the clan system as fortunes changed hands after the Highland Clearances. Their lives were as rugged as the lands they ruled. Filled with craggy inlets, mist-covered mountains, and broody glens, their land lends way to legends.

Mackenzie’s, once the strongest clan in the north of Scotland, reigned for centuries. From rich, warlords to cash strapped landlords, their story portrays the end of the clan system as fortunes changed hands after the Highland Clearances. Their lives were as rugged as the lands they ruled. Filled with craggy inlets, mist-covered mountains, and broody glens, their land lends way to legends.

I went to Cambridge, the prestigious medieval university, only as a tourist, but boy did I get educated. Though my former students have attended these hallowed grounds, I felt like a dunce when I realized Cambridge was not one central institution, but actually 31 different colleges under the administrative umbrella of the University. The colleges, established between the 11th and 15th centuries, have unique, individual histories.

I went to Cambridge, the prestigious medieval university, only as a tourist, but boy did I get educated. Though my former students have attended these hallowed grounds, I felt like a dunce when I realized Cambridge was not one central institution, but actually 31 different colleges under the administrative umbrella of the University. The colleges, established between the 11th and 15th centuries, have unique, individual histories.

cheese rolls, salt & vinegar crisps (chips) were followed by sweets – brownies, French cakes – pink, chocolate and yellow frosted squares and strawberries.

cheese rolls, salt & vinegar crisps (chips) were followed by sweets – brownies, French cakes – pink, chocolate and yellow frosted squares and strawberries. rchitecture, and known for it stained glass windows whose refracted light creates incredible beauty under the vaulted ceiling. The chapel, a Tudor masterpiece, commissioned by Henry VII, was completed under Henry VIII reign.

rchitecture, and known for it stained glass windows whose refracted light creates incredible beauty under the vaulted ceiling. The chapel, a Tudor masterpiece, commissioned by Henry VII, was completed under Henry VIII reign.

When my son’s British fiancé told us we were celebrating their engagement by going punting in Cambridge, I imagined kicking the pigskin around a ballpark. But the English don’t play American football. Then I thought it must have something to do with rugby, as her brother-in-law is an avid rugby man.

When my son’s British fiancé told us we were celebrating their engagement by going punting in Cambridge, I imagined kicking the pigskin around a ballpark. But the English don’t play American football. Then I thought it must have something to do with rugby, as her brother-in-law is an avid rugby man. A person navigates by standing on the till (known as the deck) at the back, not paddling, but poling. It looks easy. It’s not. Imagine trying to propel a dozen hefty passengers forward by pushing off the river bottom with a pole vault stick.

A person navigates by standing on the till (known as the deck) at the back, not paddling, but poling. It looks easy. It’s not. Imagine trying to propel a dozen hefty passengers forward by pushing off the river bottom with a pole vault stick.

“On your right is St. John’s,” our guide said, “one of the oldest and most celebrated colleges in Cambridge.”

“On your right is St. John’s,” our guide said, “one of the oldest and most celebrated colleges in Cambridge.”

On the square across from the clock tower, the Queen Anne style White Hart, built on a Tudor foundation, remains the soul of the Georgian market town dating back to the 11th century. The hotel’s name, Hart, a term for stag used in medieval times, represented the most prestigious form of hunting. Royalty from London tracked these animals in the woods around Ampthill, a day’s carriage ride from the city.

On the square across from the clock tower, the Queen Anne style White Hart, built on a Tudor foundation, remains the soul of the Georgian market town dating back to the 11th century. The hotel’s name, Hart, a term for stag used in medieval times, represented the most prestigious form of hunting. Royalty from London tracked these animals in the woods around Ampthill, a day’s carriage ride from the city. The hotel, which over time withstood raids, conflicts and fires, has been restored in the style of an old coaching inn. The front door opens to the bar where cozy tables fill nooks like in a traditional pub, while the back rooms serve as dining areas. The former stables, now a dining hall, accommodate groups for banquets and receptions.

The hotel, which over time withstood raids, conflicts and fires, has been restored in the style of an old coaching inn. The front door opens to the bar where cozy tables fill nooks like in a traditional pub, while the back rooms serve as dining areas. The former stables, now a dining hall, accommodate groups for banquets and receptions.

Mamie’s house overlooks the quay of Trouville, France, a fishing village where inhabitants exist in rhythm with the tides and the ebb and flow of tourists flooding her Normandy beach.

Mamie’s house overlooks the quay of Trouville, France, a fishing village where inhabitants exist in rhythm with the tides and the ebb and flow of tourists flooding her Normandy beach.

The windows on one side of the apartment face the colorful, lively, bright main street alongside the Touques River; the other side’s windows look onto the darker Rue des Ecores.

The windows on one side of the apartment face the colorful, lively, bright main street alongside the Touques River; the other side’s windows look onto the darker Rue des Ecores.

Every nook and cranny remained filled with mementos triggering happy memories from Mamie’s giant dinner bell, to her French cartoon collection, to her lumpy, duvet covered beds. Artwork and photographs, showing the chronology of marriages, birthdays, baptisms, and graduations, covers every inch of wall space.

Every nook and cranny remained filled with mementos triggering happy memories from Mamie’s giant dinner bell, to her French cartoon collection, to her lumpy, duvet covered beds. Artwork and photographs, showing the chronology of marriages, birthdays, baptisms, and graduations, covers every inch of wall space.