Though she was 94 and ready to go, we are never prepared to say that final farewell to our mothers. On the day we buried our beloved Mamie, we were overcome with waves of sadness that come and go like the tide crashing the shores of Trouville by the Sea where she lived for over 6 decades. Fleeting memories of her emerged like rays of sunshine poking through the dark clouds.

Though she was 94 and ready to go, we are never prepared to say that final farewell to our mothers. On the day we buried our beloved Mamie, we were overcome with waves of sadness that come and go like the tide crashing the shores of Trouville by the Sea where she lived for over 6 decades. Fleeting memories of her emerged like rays of sunshine poking through the dark clouds.

Mamie cut the quintessential image of a traditional French woman, “toujours bien coiffée”, scarf wrapped around her neck, wicker basket swinging on her arm, bustling off to market to banter with the local merchants for the best cuts of meat and finest cream. No one would dare try to pull one over on Mamie when it came to selling second rate fruits and vegetables, only the finest for serving her family.

Though she had a difficult childhood, she was never bitter about her lot in life. After meeting at a tea dance popular after the war, she married Guy Lechault in 1951. She had 2 beautiful daughters and one fine son, who became my loyal, loving husband.

Growing up during the hard times between two world wars, she dedicated her life to raising her family making sure her children never had need for naught. Family was the center of life and her 5 grandchildren were the apples of her eye. She was so proud of them; they were so fortunate to have had her as part of their lives during their growing up years.

Nathalie her eldest grandchild remembers when she was old enough to drink alcohol and had her first glass of wine à table with her French family,

“Mamie was so delighted,” Nat says, “it was as if the messiah came!”

Mamie made everyone’s favorites dishes, often serving 5 different menus when the kids were little, but they all grew up appreciating healthy food and mealtime remained sacred-a time to gather round the table to tell stories, talk about food and savor the tastes.

As soon as we finished one meal, Mamie, a woman who never served a sandwich in her life, would ask, “What would you like for lunch tomorrow?”

Lunch meant dinner in the old-fashioned sense — a five-course meal with a starter, main course, cheese platter, dessert and coffee with chocolates that she had hidden for special occasions. Then she would set out thimble sized glasses and poured “just a taste” of her homemade plum liquor. We had barely cleared the table before Mamie started preparing for the next feast, scurrying back around to the village shops filling her wicker basket with fresh supplies from the butcher, the baker and the creamery.

We had barely cleared the table before Mamie started preparing for the next feast, scurrying back around to the village shops filling her wicker basket with fresh supplies from the butcher, the baker and the creamery.

She lived in a 17th century fisherman’s flat chiseled into the falaise on the quay of Trouville. The small rooms were stacked on top of each other like building blocks connected by a creaky, winding wooden staircase.Her home was her castle; the dinner table her throne, although she never sat down; she was always so busy serving others.

No matter how crowded the 12” by 14” living room, there was always space to squeeze in around the big wooden table that could always accommodate one more.

Mamie could be stormy with a sharp tongue that you never wanted to cross, but she was also sunshine filled with warmth and the first to offer consoling words in times of trouble. Ever since my car accident in France 40 years ago, like a mother hen she welcomed into her family nest and watched over me as if I were a baby chick with a broken leg.

Mamie could be stormy with a sharp tongue that you never wanted to cross, but she was also sunshine filled with warmth and the first to offer consoling words in times of trouble. Ever since my car accident in France 40 years ago, like a mother hen she welcomed into her family nest and watched over me as if I were a baby chick with a broken leg.

Mamie was the sun and the sea, the wind and the rain, the beach, the boardwalk, the open market, the fish sold fresh off the boat on the quay. She was Camembert, strawberries and cream, chocolate mousse, apple tart and homemade red current jelly.

Mamie was the sun and the sea, the wind and the rain, the beach, the boardwalk, the open market, the fish sold fresh off the boat on the quay. She was Camembert, strawberries and cream, chocolate mousse, apple tart and homemade red current jelly.

She may be gone, but she will never ever be forgotten. Our every memory of Normandy is a memory of Mamie, the matriarch, the heart of our French family.

Trouville sur Mer, Normandy, France

https://pattymackz.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Jirai-revoir-ma-Nomandie-2.mov

Mamie’s house overlooks the quay of Trouville, France, a fishing village where inhabitants exist in rhythm with the tides and the ebb and flow of tourists flooding her Normandy beach.

Mamie’s house overlooks the quay of Trouville, France, a fishing village where inhabitants exist in rhythm with the tides and the ebb and flow of tourists flooding her Normandy beach.

The windows on one side of the apartment face the colorful, lively, bright main street alongside the Touques River; the other side’s windows look onto the darker Rue des Ecores.

The windows on one side of the apartment face the colorful, lively, bright main street alongside the Touques River; the other side’s windows look onto the darker Rue des Ecores.

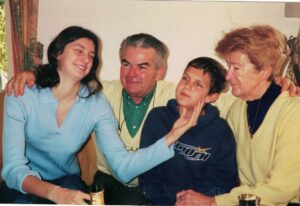

Every nook and cranny remained filled with mementos triggering happy memories from Mamie’s giant dinner bell, to her French cartoon collection, to her lumpy, duvet covered beds. Artwork and photographs, showing the chronology of marriages, birthdays, baptisms, and graduations, covers every inch of wall space.

Every nook and cranny remained filled with mementos triggering happy memories from Mamie’s giant dinner bell, to her French cartoon collection, to her lumpy, duvet covered beds. Artwork and photographs, showing the chronology of marriages, birthdays, baptisms, and graduations, covers every inch of wall space.